ACL Surgery for Ruptured or Torn ACL – Symptoms, Surgery & Recovery

By Mr. Sam Rajaratnam FRCS (Tr. & Ortho)

The Ligaments –

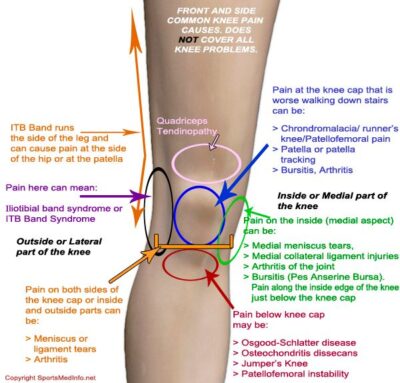

The strong, flexible, fibrous and elastic connective tissue which connect one bone to another, provide stability and support joints. The cruciate ligaments are two of the four ligaments in the knee joint. These four ligaments support the joint structure and hold it in the correct alignment. The ligaments comprise the medial and lateral collateral ligaments, on the inside and outside of the knee respectively, which give sideways stability to the knee joint, and the anterior and posterior cruciate ligament at the front and back of the knee.

The Cruciate Ligaments

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) lies towards the front of the knee and has attachments at the front of the tibia. The posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) lies towards the back of the knee and attaches to the back of the tibia. The ACL and PCL run in opposite directions to form an ‘X’ within the knee capsule. The ACL prevents forward movement of the tibia under the femur and also resists rotational overloading. The PCL prevents backwards movement of the tibia under the femur and is the principal stabilising ligament of the internal knee.

Causes of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury

ACL injury is typically caused by abnormal stress being put on the knee joint. This can occur by twisting the knee joint while the tibia is in a fixed position, a sudden shock impact, or a sudden stop or change of direction.

The severity of the damage can vary; in relatively mild cases the ligament could just be overstretched with the ligament still intact. However in more severe cases there could be a tear in the ACL. It is common for damage to the ACL to be accompanied by other damage, such as damage to the menisci, damage to the medial and lateral collateral ligament, damage to the joint capsule or the articular cartilage covering the bones in the knee joint. There could also be bruising to the bones beneath the cartilage or damage to the ends of the femur and tibia. In addition complications can also develop after ACL injury such as osteoarthritis of the knee.

It is observed that the proportion of ACL injury is higher in women than men by a factor of 2 to 10. In addition a number of studies have suggested that there may be a significantly higher incidence of ACL injury in women when engaged in certain sports such as football, skiing and athletic events which involve jumping, landing and twisting. There are possibly several factors involved in this phenomenon:

- Women have a narrower intercondylar notch (the groove in the femur through which the ACL passes), which restricts ACL movement especially during twisting movements.

- The ACL in women tends to be smaller than in men making it more prone to injury.

- Women have a wider pelvis which can affect the quadriceps angle (the angle at which the femur meets the tibia). This affects the alignment of the knee with a tendency to angle the knee inwards (valgus alignment), and this can put added stress on the ACL when subject to pressure or twisting.

- Women’s pelvic and femoral muscles tend to be weaker than men’s so that, during twisting or abrupt movement, less force is absorbed by muscle and more by the knee joint.

- Women’s knees tend to be more flexible than men’s, so that they are prone to hyperextension putting more pressure on the knee’s muscle fibre and connective tissue.

- There is the possibility that women may be more prone to ACL injury in the first part of their menstrual cycle before ovulation.

Reducing the Risk of ACL Injury

The incidence of ACL injury is higher in individuals who participate in athletic activities, and the possibility of injury is heightened if the muscles are not warmed up before strenuous exercise and warmed down by stretching after exercise.

The risk of ACL injury can be considerably reduced by undertaking exercises to improve the strength of certain muscles, and by studying techniques to avoid injury prone situations. Exercises which are advantageous include those to strengthen the pelvis, the lower abdomen and the leg muscles. Training techniques for the position of the knees in jumping and landing, twisting and turning are all particularly helpful.

Symptoms of Anterior Crucament Ligament Injury

Symptoms of an ACL injury can include:

- A feeling that the knee is giving way under normal weight bearing conditions.

- A popping sound in the knee.

- Swelling of the knee after a few hours.

- Loss of mobility and range of motion.

- Discomfort when walking.

If you suspect that you have damaged a ligament in your knee you should apply ‘RICE’ – Rest, Ice to reduce the swelling, apply a Compression bandage and Elevate the knee. Complete immobilisation is not advised as moving the knee helps to prevent stiffness and the possibility of muscle atrophy.

Treatment of ACL Injury

When the injury is clinically assessed your doctor will need to know how the injury came about in order to help determine its cause.

Physical Examination. The physical examination consists of inspection, palpation, and assessment of the knee joint function. The doctor will examine both knees to see if the injured one is visibly different to the normal knee, and manipulate the knees to determine if the injured knee articulates in an abnormal way.

If an ACL injury is suspected the doctor may perform the ‘Lachman Test’, the ‘Anterior Drawer Test’ or the ‘Lever Sign Test’, to confirm the diagnosis, all of which involve manipulation of the lower leg. Palpation of the joint line can also determine if there is any damage to the lateral meniscus.

Functionality tests determine the stability of the joint and ACL, and can assess any degree of joint separation.

Diagnostic Imaging. X-ray (radiograph) will not show soft tissue such as the ACL, but will often be used to eliminate a break in the bone. An MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan would be employed because this will show bone and soft tissue, including any bruising to the bone which might be present.

Treatment of a Partially Torn ACL Injury

The ACL is composed of bundles of collagen fibres so it is possible to have a partial tear in the ligament with just one bundle affected. Patients who have partial tears can sometimes return to their previous activities without feeling that their knee joint is weak or giving way, but for others the knee will feel unstable, preventing normal sporting activity. If the knee does feel unstable, and you return to normal sporting activities, you may risk further injury by tearing other structures in the knee such as the medial or lateral meniscus. In addition there is the further risk of articular cartilage lesions later in life.

A partial tear poses the difficult question of whether to have surgery or not. The decision will rest on the doctor’s assessment of the extent of ACL tear, the degree of instability, and whether you lead an active life or not. It may be decided that the tear is not too debilitating for your lifestyle, the instability of the knee is not too serious, and non-surgical management of the torn ACL is preferable. However, if instability continues it may result in a secondary injury.

Non-surgical management

In the case of non-operative treatment the prognosis is often good, although a partial tear can take a number of months of recovery and rehabilitation. A course of physiotherapy, advice about how to control instability problems, and possible orthotic management may be all that is required. The aim of physiotherapy would be to regain full control of the knee and to walk normally again. It is particularly important, whether there is subsequent surgery or not, that the knee can undergo full hyperextension so that the injured knee extends as fully as the uninjured knee. There is a heightened risk of developing osteoarthritic change in the knee if it is unable to fully extend for a long period of time. It should be remembered, however, that if surgery is postponed and it is later decided that surgery is necessary, the delay could cause further damage to the knee.

Treatment of a Ruptured ACL

A fully ruptured ACL means that there is a complete disruption of the ligament between the femur and tibia. It may be that the rupture, despite physiotherapy, orthotics, and the possibility of lifestyle change, leaves an instability which reduces quality of life. In this case a complete tear in the ACL has the prognosis for a less successful outcome without surgical intervention. Surgery is also usually recommended in the case of patients who have ACL injury coupled with other damage to the knee.

ACL in Children

It has been considered, and is still a belief in some quarters, that surgery should not be recommended in the case of children or adolescents, because they have not reached skeletal maturity and there is the danger of damage to growth plates. However, more recently, it is suggested that non operative management has led to the subsequent need for meniscal surgery and treatment for cartilage lesions. There has also been the incidence of chronic instability and poor outcomes. Many paediatric orthopaedic physicians today would recommend the intervention of surgical reconstruction for children after confirmation of a torn ACL by a pivot shift test (rotating the tibia and femur to test for instability), to assess the degree of incapacitating dysfunction in the knee.

ACL Surgery

Grafts

ACL tears cannot be sewn together because this type of repair has been shown to fail. The common surgical procedure is to insert a graft. Tunnels are drilled through the femur and tibia, and the graft is passed into the knee joint via these tunnels and secured. Grafts are taken from ligaments and can either be allografts – taken from a cadaver, or autografts – taken from the patient’s own tissue. Alternatively a tubular synthetic graft can be used.

Autografts are favoured because with allografts there is the possibility of the transmission of disease. In addition it is sometimes thought that the irradiated and chemically treated allografts, which are supplied by many companies, tend to eventually weaken. Also some studies show a higher failure rate with allografts than with autografts. However, allografts are becoming more popular and do have the advantage of eliminating the pain associated with autograft harvesting. They are also quicker for the surgeon to graft and involve smaller incisions. Allografts and synthetic grafts tend to be used for revision surgery and when patients need more than one knee ligament to be reconstructed.

In the case of autografts various tendons could be used including the quadriceps, patellar and hamstring tendons, with the hamstring tendons often being favoured.

Quadriceps tendon grafts are harvested from the middle third of the quadriceps tendon at one end, with a bone plug from the upper end of the patella at the other. This provides a larger graft suitable for taller and heavier patients. It tends to be used in revision surgery, but has a high incidence of postoperative pain at the front of the knee and a possibility of fracture of the patella.

A new ACL can be made with the middle third of the patellar tendon. This graft has a plug of bone taken from the patella on one end and the tibia on the other end. These plugs of bone provide a seating for the graft. However there does appear to be a likely incidence of postoperative pain behind the knee when using this graft.

Hamstring tendon grafts are becoming more popular, and specialists are often of the opinion that they are to be preferred. They argue that the side effects are significantly less than patellar tendon grafts, and they are also easier to harvest. Tendons from the semitendinosus and gracilis muscles in the hamstring are harvested, doubled over to form a four strand graft and sutured together at both ends. The graft is then fixed to the femur and tibia. This is a day surgery procedure and patients, who are invariably able to bear their own weight immediately after surgery, can leave hospital a few hours after the operation.

Synthetic ligaments were developed in the 1980s and 1990s for ACL surgical reconstructions, and are now in their third generation. Various trials have included carbon fibre, Dacron and PTFE (Polytetrafluoroethylene), but products are still under development, and a perfect synthetic graft has yet to be found. Work is ongoing on other types of artificial ligament.

Recovery from ACL Surgery

The operation to replace the ligament is only part of the process, full recovery can take more than a year. ACL surgery will put the frame of the reconstructed ligament in place, but it is the body itself that will biologically remodel this frame of tendons into a functioning ligament. The biological and mechanical changes in the healing graft is termed ligamentization, and while it is progressing the patient may experience weakness and impaired function in the knee joint. This is a normal part of the process and should not be worrying.

Before the operation

Before surgery there is essential work that patients should do to prepare themselves for the the operation which will lead to optimum postoperative recovery. The preoperative period may last weeks or months because all swelling should have subsided and a full range of movement should be regained before surgery can take place. Also the quadriceps and hamstring should be exercised so as to be as strong as possible, and the patient would be advised to engage in a course of physiotherapy and some low-impact exercise such as swimming, cycling or gym – running and jumping should be avoided. Physiotherapy exercises learned now will help with post operative exercises, and strengthening muscles at this stage will make recovery from surgery quicker, easier and give the best chance for regaining full mobility.

Rehabilitation

There are six stages in the rehabilitation process. Approximate time intervals after the operation are allocated to each stage, but the stages should be measured in goals rather than time. The final goal being a return to normal functioning.

Stage 1. Immediately post operation to 14 days after the operation

Straight after surgery as much weight bearing as is comfortable and immediate mobilisation are beneficial. The wound will be healing, so bruising, swelling and redness in the area of trauma are normal, and should be managed with ice and elevation of the leg. The goals for this stage include a full range of motion of the joint and full weight bearing on the leg. Gentle exercises which work on the hamstring and the hamstring/quadriceps muscle groups at the same time are begun in order to help to restore co-ordinated muscle function. The beginnings of a return of muscle control, and the ability to fully extend the limb are goals, together with reduced use of crutches and a return to normal walking action.

Stage 2. From 2 to 6 weeks after the operation

Exercises concentrate on development of good muscle control, particularly the hamstring and quadriceps muscles. These exercises are intensified both in duration and variety. Work begins to help the patient to be aware of the positioning of the knee and to regain balance and strength in the joint. If a return to normal walking action has not yet been achieved more work is done to accomplish that. A cold compression knee wrap can be used to reduce any persistent swelling in the joint.

Stage 3. From 6 to 12 weeks after the operation

Work focuses on exercises for the sensors that provide information about the angle of the joint, muscle tension and the position of the joint in space. Other goals are to begin work on neuromuscular control in order to relearn movement patterns and skills, and exercise for the leg muscles to improve endurance, strength and confidence.

Stage 4. From 12 weeks to 5 months after the operation

The foremost task is to improve neuromuscular function. Work continues on strengthening all the leg muscles, and agility is introduced. Agility is incorporated with exercises to improve the awareness of movement of the joint in space. Skills to enable the patient to re-enter sporting activities are introduced into the programme and confidence is improved.

Stage 5. From 6 to 12 months after the operation

This stage concerns continued preparation for a return to sporting activities, including working on techniques and skills, and improving confidence, strength and endurance. Exercises include warm up, rapid and repetitive stretching/contracting the muscles, strengthening the muscles and improving agility.

Stage 6. From 12 months after the operation onwards

The final stage is a return to sporting activity with some precautions including using warm up neuromuscular exercises which rehearse body movements about to be undertaken. The neuromuscular programme is continued and a measured approach to reintroduction to full sporting activity is undertaken.